What’s in Mrs. Hale’s Receipts for the Million 1857?

1199. Cheap Ginger Biscuits.—work into quite small crumbs three ounces of good butter, with two pounds of flour; then add three ounces of pounded sugar

Writing historical fiction

Why Do I write Historical Fiction? I love history. (And ginger cookies were very popular in 1857) I grew up on family stories from my ancestors arrival in Newburyport, MA in 1638 to my great grandfather assistant surgeon at the Battle of Gettysburg and the pioneer stories of my Nana and her mother in the last 19th century.

My guest author, Helena Page Schrader writes award-winning historical fiction which I think you should know about. She has written about the Crusades and ancient Sparta, but recently has written about WWII and the aftermath. Here, she focuses on a subject term I didn’t know about, “moral fibre” (moral fiber to Americans) I’ll let her speak, so welcome, Helena.

What is “moral fibre”?

The inception of my novel Moral Fibre was a classic case of genuine inspiration. I can remember the exact moment when inspiration struck. I was sitting before the fire with my husband, sipping a glass of wine and feeling rather pleased with myself for wrapping up a book that combined two novellas under the joint “umbrella” title of Grounded Eagles. Suddenly I realized that something was missing. I needed a third novella, and it had to tell the story of a young man officially labelled “lacking in moral fibre” (LMF) for refusing to fly on a combat mission against Germany.

I’d seen reference to LMF while researching my novel on the Battle of Britain (Where Eagles Never Flew). However, I didn’t know much about the concept — except that men suffering from what we would today call PTSD were apparently labelled “LMF” (i.e. “cowards”) and subjected to severe disciplinary action. Before I could look into that, however, I knew I needed to understand more — that is to systematically research — the British strategic bombing offensive, Bomber Command, bomber aircraft, bomber crews, and bomber training because up to then, my research had been on Fighter Command, Transport Command (for my work on the Berlin Airlift), and women pilots.

The first thing I learned was that casualty rates among bomber crews were appalling. Although chances of survival varied over time, by the end of the war a total of 57,205 aircrew or 46% of all men who flew with Bomber Command had been killed in action. In addition, 8,403 had been invalided, and 9,838 taken prisoner. The effective casualty rate was 60%.

Yet all the men who flew with the RAF were volunteers, and only one in ten of the men in the RAF actually flew. In other words, it took nine men on the ground to support (recruit, train, equip, house, feed, and maintain the equipment of) each man in the air. “Aircrew,” the men who flew in whatever capacity (i.e as pilots, navigators, bomb aimers, wireless operators, flight engineers or air gunners), were all viewed as an elite and enjoyed higher status than their non-flying comrades.

Winning the coveted “aircrew brevet” was not easy. Many candidates “washed out” before qualifying. Pilot, navigator and wireless operator training took up to two and a half years. Aircrew training was also dangerous. Over 8,000 men training for Bomber Command were killed and 4,200 seriously injured in training accidents. Yet the RAF always had more volunteers than they could absorb.

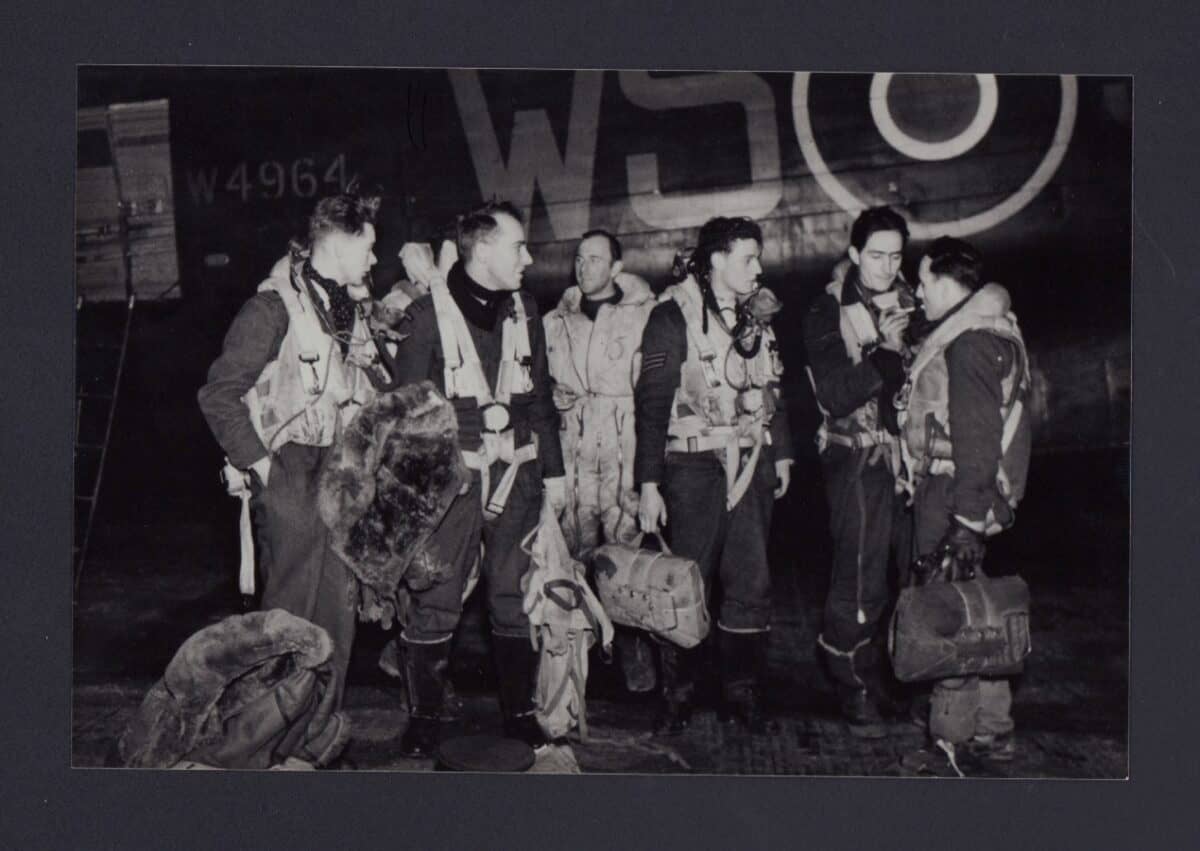

Courtesy International Bomb Command Centre Digital Archive

The horrors of war

Yet the realities of combat — brushes with death, the loss of friends — inevitably took their toll. Some of these carefully selected and meticulously trained volunteer aircrew at some point in their career refused to fly. The refusal to volunteer was hardly a breach of the military code, however, so the RAF decided that men who refused to fly without a valid medical reason or “lost the confidence of their commanding officer” should be immediately posted off their squadron and subjected to disciplinary measures for “lacking moral fibre.” The term was intentionally derogatory to discourage “malingering,” and rumors soon spread that drastic, degrading and humiliating punishment followed a posting for LMF. The fear of being posted “LMF” caused some men to fly beyond their limits.

My research, however, turned up some fascinating studies published in the Journal of Mental Science and the British Journal of Military History. These drew on extensive studies conducted during and after the war. Published under such intriguing titles as Anatomy of Courage, Courage and Air Warfare and War of Nerves, these studies revealed a far highly nuanced and sophisticated picture of the issue.

Meanwhile, I was immersed in writing a book that completely absorbed me mentally and emotionally. You see, what was really going on was that I was being asked to write a specific story, Kit Moran’s story. I don’t know if that was his real name, but it is the name used in the novel to describe what happened to a young man who was using me as his voice. That may be difficult for some readers to understand, but it is the only way I can explain what was happening.

After several intense months of researching and writing, I completed a novella to be included in the Grounded Eagles anthology/trilogy. Yet no sooner had I finished it than I realized that the novella (entitled “Lack of Moral Fibre”) was only the teaser, or introduction, for the longer work. The novella explained, through many flashbacks, what had caused Kit to refuse to take part in an operation against Berlin in late November 1943; the real story, however, was what happened to him afterwards.

There was nothing I could do but change all my plans, push back other work, and focus on telling the rest of Kit’s story. This became the novel Moral Fibre, which follows Kit’s return to operational flying. Now a trained pilot, he is responsible for the lives of six other men — and he is prepared to die for them. Yet his desire for life is kindled by his love for Georgina, a trainee teacher who has already lost her fiancé in the air war against Hitler and is afraid to give her heart again. The result is a novel that explores the many faces of courage, grief, faith — of course — and moral fibre.

Awards for Moral Fibre

Moral Fibre won a Maincrest Media Award, earned SILVER in the Historical Fiction Company Book Awards, was a finalist for a Book Excellence Award and was a Distinguished Favorite in the Independent Press Awards. Maincrest Media writes: “A perfect blend of history, romance, and inspiration….” The Foreign Service Journal calls it “a tribute to those who fought for freedom.” Kirkus Reviews concludes, “A richly textured, absorbing war tale that works equally well as a touching love story.”

Thank you, Helena, for the post. I learn something new every day about WWII. It’s important to know because, history rhymes.